Virufy Asymptomatic COVID-19 Detection - Cloud Solution

The Team

- Taiwo Alabi

- Alex Li

- Chloe He

- Ishan Shah

I. Problem Definition

By March 2021, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has infected nearly 120 million people worldwide and claimed more than 2.65 million lives [1]. Moreover, a large percentage of cases were never diagnosed because of hospital overflows and asymptomatic carriers. According to a recent study published in the JAMA Network, an estimated 59% of all COVID-19 transmissions may be attributed to people without symptoms, including 35% who unknowingly spread the virus before showing symptoms and 24% who never experience symptoms [2]. Therefore, in order to prevent further spread of the virus, it’s crucial to have screening tools that are not only fast, accurate, and scalable, but also accessible and affordable to the general population. However, such tools do not currently exist.

Since spring 2020, AI researchers have started exploring the use of machine learning algorithms to detect COVID in a cough. Researchers at MIT and the University of Oklahoma believe that the asymptomatic cases might not be “truly asymptomatic,” and that using signal processing and machine learning methods, we may be able to extract subtle features in cough sounds which are indistinguishable to the human ear [3]. In the past year, there have been a number of related projects around the world: AI4Covid-19 at the University of Oklahoma, Cough against COVID-19 at Wadhwani AI, Opensigma at MIT, Saama AI research, among others.

However, existing cough prediction projects have varying performances and often require high-quality data because the models were trained on audio samples that were recorded in clinical settings and appropriately preprocessed [4]. Some models do not aim only at COVID detection but at all respiratory conditions, which makes it harder to balance between different performance metrics and therefore unsuitable to the needs of minimizing false negatives for the purpose of COVID prevention. These challenges motivated our project, as we hope to build a cloud-computing system better suited for detecting COVID in various types of cough samples and a prescreening tool that is easily accessible, free for all, and produces nearly instantaneous results.

II. System design

Virufy cloud needed an online prediction machine learning system with a low-latency inference capability. We also needed to comply with HIPAA privacy rules with regards to health data collection and sharing.

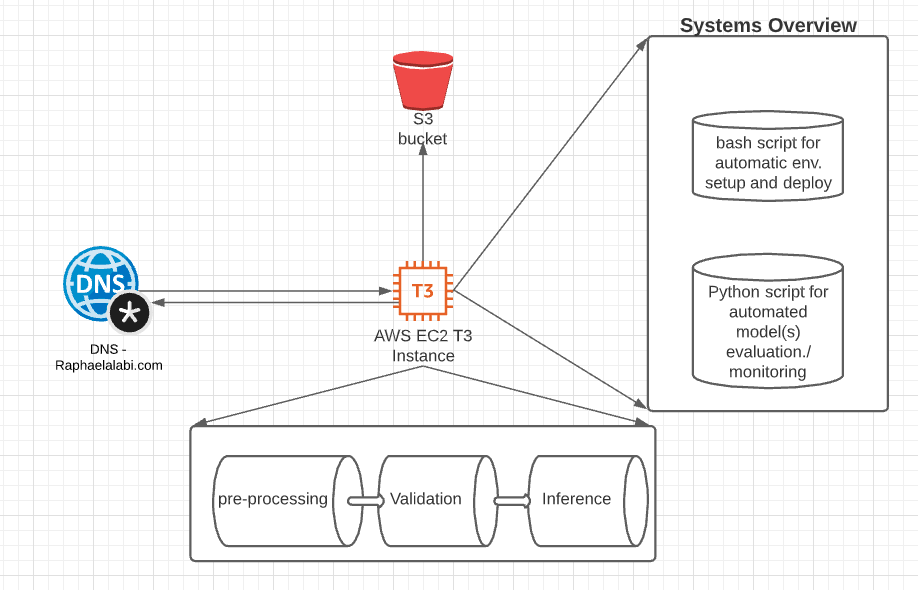

Hence the machine learning system that we designed is hosted in the cloud on a beefy EC2-t3-instance with GPU acceleration. An elastic IP address was assigned to the EC2 instance and the main app was served at port 8080. A DNS name rapahelalabi.com was used to redirect all traffic to the elastic IP address through the open port.

To comply with HIPAA privacy rules, we decided not to provide the option for users to enter personal information. This ensured complete anonymization of the entire process since data from user, user waveform .wav file, is run through the inference engine and subsequently not stored anywhere in the pipeline.

The data flow diagram for the system is shown above. With the DNS forwarding traffic to the EC2 instance. The EC2 instance does 3 processes to reduce latency including:

- Converts waveform (.wav file) to Mel-frequency spectrogram and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs)

- It also incorporates a pre-trained XGBoost model from COUGHVID to help validate if there is an actual cough sound in the waveform file.

- It uses the inference model to infer the probability of the Mel-frequency spectrogram and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) containing having COVID-sound biomarkers or not.

These 3 processes run asynchronously and the current latency is ~2sec, from uploading a cough sound to getting a positive or negative result output.

The system also has an automated model deployment script that can automate deployment with only one line of code to an Ubuntu deep learning AMI image. The automated script makes it so much easier to deploy by taking care of all dependencies and co-dependencies during deployment. In addition, we also have an automated model validation script that can evaluate performance of many models and give their specificity and sensitivity to COVID-19 using a customized dataset that is also downloaded into the EC2 instance and kept in the repo.

We needed a t3 instance with GPU acceleration because the core of our inference engine uses a convolutional neural network that is accelerable with GPU. We also decided to separate the inference step from the pre-processing and input data validation steps to ensure modularity and error tracking.

The machine learning system we built also has an error-tracking log file in the server that could be used to debug the system when necessary. By incorporating error logging capability, automated model evaluation and validation, automated model deployment, and model inference, we have built and demonstrated a well-rounded system that can serve users from around the world at low latency speed. In addition the model evaluation allows for continuous integration and deployment- CI/CD- since it allows uploading many models and evaluating those models in the cloud. Thus enabling an almost seamless switch from one inference algorithm to another inference algorithm.

A couple of flaws that the system currently faces in production would be susceptibility to attacks. The URL to our EC2 instance is public and we made the port open to the entire world. Although this made it easy to deploy and serve the model it also exposes us to DOS attacks.

In addition, the system is currently not scalable, horizontally. To enable horizontal scaling using a load balancer on AWS we would need to integrate and use EBS (Elastic Beanstalk).

III. Machine Learning

We started out with the hypothesis that cough sound from COVID-19 positive carriers could be differentiated from cough sound from unaffected people. We pre-processed cough recordings from two open-sourced COVID-19 related datasets, Coswara[5] and COUGHVID[6]. Extracted features include the recording waveform, age, and gender. We take all positive samples and randomly selected subsets of negative samples from the datasets to compensate for class imbalance. We also tried taking all samples and assigning different class weight combinations, even though this approach did not perform as well.

Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) and mel-frequency spectrograms [7] have been used to extract audio signature from cough recordings. Our main approach is to build two branches of the modelling pipeline that can handle those different engineered-features separately, which are sequentially merged together for a single binary classification task.

We received 39 numerical coefficients from MFCCs as output, for which we built a two-layer dense model. The spectrograms are in image format (64x64x3),for which an ImageNet approach can be applied. We attempted numerous pre-trained models on ImageNet, including ResNet50, ResNet101, InceptionV2, DenseNet121, etc. ResNet50 was shown to perform the best. The output of the pre-trained base model is passed to a global average pooling layer, a dense layer and a dropout layer. We merged the outputs from a two-layer dense model for MFCCs and Convolutional Neural Net model, and passed the merged output through another two models with a shrinking number of nodes. The final output is a single node with sigmoid activation function.

Alternatively, we tried automatic neural arectural search using AutoKeras. This is to systematically test for other architectures. However, we did not achieve the same level of performance on the test set obtained by the handbuilt architecture in the past paragraph.

The dataset was randomly shuffled and split into 75% training, 15% validation and 15% test set. During the training, we grid-tuned different optimizers until determining that Adam works best. After training, we found the best cut-off for binary classifications with Youden’s J statistics (Sensitivity + Specificity) [7].

IV. System evaluation

| # samples | Accuracy | Weighted F1 | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Female | 864 | 0.7049 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| Male | 1,968 | 0.6951 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.65 |

| # samples | Accuracy | Weighted F1 | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| <= 20 | 288 | 0.7222 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.64 |

| 21-40 | 1,680 | 0.7065 | 0.75 | 0.96 | 0.66 |

| 41-60 | 576 | 0.6867 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| > 60 | 48 | 0.7292 | 0.65 | 1 | 0.67 |

Table 1: Sliced-based analysis results using an optimized cutoff of 0.012245 across a) gender groups and b) age groups.

We obtained the cutoff based on AUC analysis on the test set. At the threshold, the test set performance achieves 79.71% sensitivity and 49.20% specificity. The FDA guidance to COVID-19 testing solution explicitly mentions that sensitivity and specificity are the main metrics [8]. We believed that sensitivity is the most important metric of success as a screening tool, as it measures how many actual COVID-positives were captured by the model. Achieving approximately 80% sensitivity shows that we can correctly identify those with COVID-19 virus with substantial success. Admittedly, we did not achieve great specificity: 49% specificity means that there is roughly one false positive for every positive prediction. However, from a public health perspective, we think it is far more costly for a restaurant to admit infected customers than to send more people to PCR tests than necessary.

We performed slice-based analysis across different age and gender groups in order to evaluate the performance of our model and address model weaknesses. We did inference on the entire dataset. Using an optimized cutoff of 0.012245, we found that the model achieved almost exactly the same accuracies and F1 scores among the male and female populations. Individuals between the age of 21 and 40 make up most of the population from which the cough samples were crowdsourced; despite large differences in the number of samples across age groups, the model was as accurate in the 21-40 age group as in the >60 age group. These results demonstrate that the cough signatures are generalizable across different gender and age groups, and that the model is not biased towards any gender or age groups.

Separately, we also created an automated system evaluation that can provide analysis of multiple models as well as their inference latencies right within the production environment. These codes run in both python and bash. By using the automated script we were able to capture 2x increase in latency in moving from a tri-layer CNN architecture to a ResNet50 architecture. However, what we gave up in latency we more than made up for in specificity and sensitivity of the algorithm. With the ResNet50 algorithm enabling a sensitivity score of 0.79 and a specificity score of 0.9, while the tri-layer CNN architecture has a sensitivity score of 0.6 and a specificity score of 0.59 in production. Analysis was performed using a separate holdout dataset that was manually culled, curated for sound veracity and sound clarity.

In addition, we evaluated the performance of the pretrained XGBoost cough validation classifier, which has some drawbacks. Specifically, the algorithm tends to misclassify audio recordings that have low-pitch or quiet coughs as non-cough files.

V. Application demonstration

We chose to make this a web application running on AWS and routed to Taiwo’s URL (raphaelalabi.com) to keep it simple for the user and have their result with a couple of clicks. The feature set of the web app is fairly simple. It consists of uploading a .wav file to the browser and clicking the “Process” button. The app could reject the input due to a wrong file format, the audio not within length boundaries (0.5 - 30 seconds), or the audio not being detected as a cough, and output the appropriate error message (image below).

If the input is accepted, based on a fixed threshold determined by model evaluation, you will reach either a “positive” or “negative” landing page after a few seconds, returning the probability that you are an asymptomatic COVID carrier and general guidelines in both cases. We decided to only have two landing pages as we did not feel confident in setting more thresholds based on limited evidence from our model evaluation.

Instructions and Images:

- Navigate to raphaelalabi.com

- Upload .wav file from your local directories and click “Process”:

That’s it! The possible errors mentioned above display a message like this and ask to re-upload:

If the model successfully processed the data, you will get one of the following landing pages specifying a “positive” or “negative” result with disclaimers and guidance:

VI. Reflection

We believe that the infrastructure that we built our system on worked well given the team members’ varying skill sets. AWS was a great fit because their deep learning EC2 instances come preloaded with Anaconda and other linux commands required for deployment of our application, cutting out the time-consuming step of installing them and properly configuring their paths. Furthermore, Taiwo, who has more experience with the platform, deploys the app through his root account, and created IAM accounts so the rest of us could easily access the same resources.

Another success was keeping the code concise through properly compartmentalizing it. Essentially, we pull the .wav file through a simple API call, run it through a preprocessing function to featurize it and verify it’s a cough, then run inference through the model loaded from an hdf5 file and trained separately from the system’s codebase. This setup allowed us to iterate our system and use Git with fewer roadblocks.

In general, our team communicated effectively over Slack and had an effective division of labor as we consistently listed the remaining action items and assigned them. However, we could have met on Zoom more and learned about each other’s components with more depth, as we spent a fair bit of time in the chat playing catch-up.

The most obvious drawback in our current system is the need for the file to be .wav, which often requires a user to manually convert the audio on a third-party website. Given a little more time, we would probably have solidified the functionality of recording within the application and/or accept and internally convert audio files of other formats.

A more subtle yet significant limitation comes from the data utilized to train and evaluate our model. The coughs could come from symptomatic carriers, not just asymptomatic, diluting our metrics. After manually listening to positive waveforms from Coswera, we could not tell if some were asymptomatic forced coughs or naturally occurring coughs from patients. We realized we cannot solve this challenge to differentiate the two because we do not have the ground truth or curated datasets from both categories.

With more time and resources, the first critical component to improve on would be model performance –prioritizing sensitivity. We could only train a few architectures and hyperparameter combinations on a limited dataset, so we would want to expand on that with more research and compute power. Also, we would learn the ins-and-outs of audio data and its different features to expand the pre-processing code, and relatedly implementing segmentation methods to reduce noise in the input. The second would be to improve the general user experience. For example, if a positive result is returned, we should return a basic analysis of the waveform explaining the model’s “decision”, and possibly route the user to a PCR test based on their current location.

We are operating under the umbrella of the larger Virufy non-profit, and hope portions of our work can be adapted into their codebase. Some of our team members are thinking about continuing to work on Virufy, and hope to see it succeed with the continued development of new features and more accurate models.

VII. Broader Impacts

This application is intended for use as a potential, fast, and accurate COVID detection using an unforced cough wave-form from an individual. We could see this used as a diagnostic tool in airports, hospitals and other health institutions, care-taker homes etc. This algorithm will come in handy in those places where fast diagnosis of COVID-19 ensures that regular traffic flow is minimally impacted by the need to ensure those coming into those institutions are not asymptomatic carriers.

A potential associated harm with using this machine learning system is that it is possible that a person with common viral pneumonia or a bad case of the flu could also be labelled by the algorithm as an asymptomatic carrier. The algorithm has not been properly calibrated with users having flu, pneumonia, and other respiratory conditions but that do not have COVID or have COVID. Our belief is that such individuals may also carry the vocal bio-maker for COVID that the model has learned and thus be classified as COVID-positive.

Lastly, our system is designed as a prescreening tool and not as a comprehensive test that would replace regular PCR or rapid testing procedures. We intended to make this as clear as possible by providing warnings and reminders on our web UI. Moreover, because the test is not 100% accurate and we do expect to see false negatives to some degree after deployment (even though we try to minimize this as much as possible), we heavily emphasize the need to continue to follow public health guidelines and quarantine procedures on our results page. For individuals who receive positive predictions, we prompt them to get a more reliable test (such as PCR) as soon as possible.

VIII. Contributions

Taiwo

- Wrote the FE interface with boot-strapped HTML/Javascript to Python.

- Wrote the deployment scripts.

- Wrote the automated testing scripts.

- Wrote the general framework of the API for pre-processing, inference.

- Engineered the use of AWS (EC2), Elastic IP address for the oncloud prediction.

- Worked on data pre-processing for the coughvid and re-wrote the initial base-line

- algorithm that gave the team a first look at the model performance.

- Worked on the initial model with multi-band CNN and DNN.

Chloe

- deployed model on EC2 and set up serving on AWS and routing to custom domain (through Namecheap)

- designed web UI (front-end)

- workshop presentation and final presentation

Alex

- Conducted deep and detailed analysis on model training, development and analysis. The output model was used in final presentation.

- Defined the cut-off threshold for the ResNet machine learning model,

- Did slice based analysis to evaluate model performance on different age and gender

- Did initial exploratory work with Sagemaker and GCP AI platform in terms of model hosting.

- Made MVP demo slides and presentation video

Ishan

- Integrated the cough validation XGBoost model into our codebase and verified its compatibility with our existing system on the EC2 instance

- Added functionalities like checking the length of the input sound

- Made UI modifications needed for final product

- Prepared appropriate examples and conducted MVP and final demos

GitHub Repo URL:

The URL to the github repo with all the code is: https://github.com/taiworaph/covid_cough

References

[1] COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). (n.d.). Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

[2] Johansson MA, Quandelacy TM, Kada S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission From People Without COVID-19 Symptoms. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2035057. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35057

[3] Scudellari, M. (2020, November 4). AI Recognizes COVID-19 in the Sound of a Cough. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-human-os/artificial-intelligence/medical-ai/ai-recognizes-covid-19-in-the-sound-of-a-cough

[4] Fakhry, Ahmed, et al. “Virufy: A Multi-Branch Deep Learning Network for Automated Detection of COVID-19.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.01806 (2021).

[5] Neeraj Sharma, Prashant Krishnan, Rohit Kumar, Shreyas Ramoji, Srikanth Raj Chetupalli, Nirmala R., Prasanta Kumar Ghosh, and Sriram Ganapathy. Coswara – A Database of Breathing, Cough, and Voice Sounds for COVID-19 Diagnosis. arXiv:2005.10548 [cs, eess], August 2020. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2005. 10548. arXiv: 2005.10548.

[6] Lara Orlandic, Tomas Teijeiro, and David Atienza. The COUGHVID crowdsourcing dataset: A corpus for the study of large-scale cough analysis algorithms. arXiv:2009.11644 [cs, eess], September 2020. URL http: //arxiv.org/abs/2009.11644. arXiv: 2009.11644.

[7] Brownlee, J. (2021, January 04). A gentle introduction to threshold-moving for imbalanced classification. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://machinelearningmastery.com/threshold-moving-for-imbalanced-classification/

[8] Center for Devices and Radiological Health. (n.d.). EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance