ML Production System For Detecting Covid-19 From Coughs

Application Link

Covid Risk Evaluation - Hosted on GCP Cloud Run

GitHub Link

CS 329S - Covid Risk Evaluation Repository

The Team

Problem Definition

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread testing has become a significant bottleneck in the efforts to monitor, model and prevent the spread of the disease. Obtaining accurate information about a person’s disease status is critical in order to isolate infected individuals and decrease the reproduction number of the virus. Unfortunately, we see four major issues with current testing regimes; first, oropharyngeal swab tests are invasive, expensive, and time consuming; second, the time required to receive test results is significant, ranging anywhere from 30 minutes for rapid swab tests to three days for PCR tests in a lab at the time of this writing; third, contamination risk is high when individuals travel to testing sites to obtain their tests, and last but not least, tests need to be administered by trained clinicians, severely limiting throughput.

In order to address current issues with testing, we developed a machine learning system to instantly test for and collect data on COVID-19 using the cough sounds recorded on the users’ personal devices. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that 5 out of 6 COVID-19 patients exhibit mild symptoms, most commonly a “dry cough” producing a unique audio signature in the lungs. Cough sound analyses have proven to be effective for diagnosing other respiratory diseases such as pertussis, pneumonia, and asthma.

Our system is deployed on Google Cloud Platform (GCP) and achieves a ROC-AUC score of 71%.

System Design

There are three different user groups for our system:

-

Regular Users

The first group involves the regular users who would like to get pre-screened for COVID-19 to inform themselves. The goal of this group is to provide them a rough idea about whether the cough-like symptoms they are experiencing could be related to COVID-19. If the cough test results signal that COVID-19 is a high possibility, the users are encouraged to seek out medical help and isolate.

-

Medical Practitioners

The second group involves medical practitioners who would like to employ a test that is both faster and cheaper before they try out more expensive, and time consuming tests. Based on the results showing the likelihood of COVID, test takers are advised to take more rigorous tests.

-

Community Administrators

The third group involves the community admins who would like to ensure the safety of their community by employing a cheaper pre-screening test for COVID.

All of our users access our app through the web using their mobile devices. For all of our users, a key consideration we kept in mind while designing our system was interpretability; we made sure to include both personalized and general explanations of how our model makes predictions. This not only informs our users but also encourages them to give back by donating their cough data for research. Interpretability is especially important for the medical practitioners using our app: even if our model fails to make the correct prediction, the methodologies and their interpretations that are being displayed can help the medical practitioners make more informed decisions.

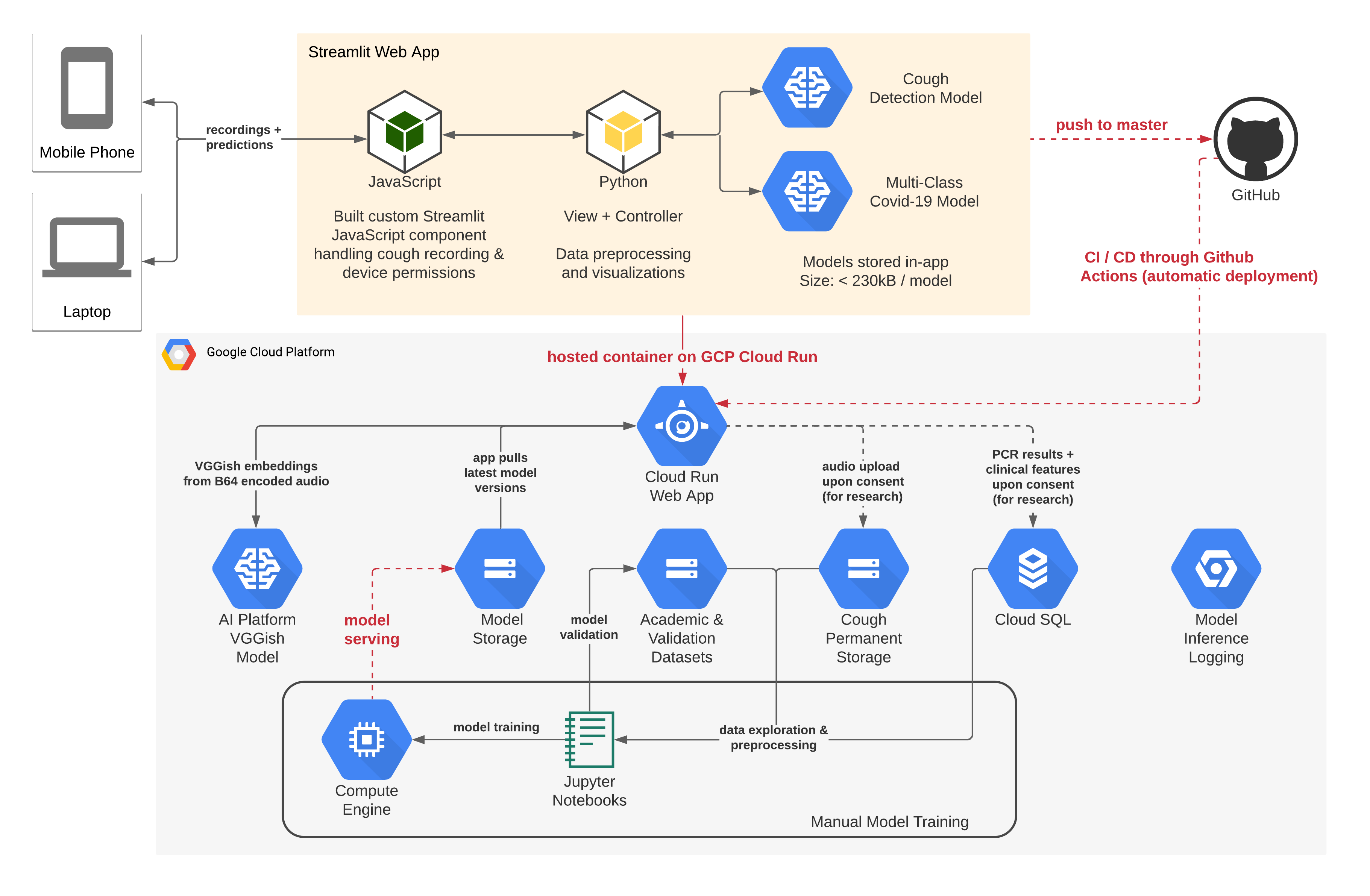

Figure 1. System Architecture on Google Cloud Platform

In order for our application to be effective in serving the needs of our target users, we needed to build various interconnected components which are shown in Figure 1. Our web-based interface allows users to record a cough sound on their laptop or mobile devices, reducing the risk of contagion and without having to download a mobile native app. Our rationale behind a web-based solution was to reduce any points of friction and avoid the perils of low uptake which COVID-19 tracing apps have experienced, further facilitating usage by wrapping the link to the web solution into a QR code. We expand more on our core system design decisions below.

Model Exploration

Developing on a Virtual Machine (VM) allowed us to collaboratively iterate on different models. Furthermore, working on GCP VMs allowed us to harness their free research TPU program to train our more compute-intensive embedding models. Lastly, gcloud operations made it easy to serve models on GCP’s AI Platform and test their performance in-app.

Model Deployment

As one of our model’s features, we used embeddings based on a commonly used computer vision model for sound data (VGGish). Given the large storage size of VGGish, we decided to run the model in the cloud using the GCP AI Platform. Once we obtained our embeddings after querying the AI Platform instance with the users’ cough audio, COVID-19 predictions were inferred in-app as this was not computationally expensive. It is important to note that also our cough detection model (sourced from Coughvid), which made sure that the user submitted a cough and not any random noise before we evaluated the audio for COVID-19, was run in-app. In addition, we built an automatic yet accurate fall-back procedure which evaluates COVID-19 risk without VGGish embeddings whenever the AI Platform is unavailable or the hosted model is shut down due to cost reasons. We are planning for the VGGish-based inference to be available continuously once our model’s accuracy is further improved.

Iterative Development and User Experience

We chose to develop our application using Streamlit because its powerful library allowed us to create an MVP version of our system quickly and to then iterate towards a more polished user experience. As sound recording was not a native feature of Streamlit, we build a custom Streamlit component in Javascript to handle recordings and device permissions which we plan to open-source to Streamlit’s components gallery.

App Deployment

We decided to host our Streamlit application as a Docker container on GCP Cloud Run because we wanted to leverage the smooth connections between the different components we had already built on GCP in addition to the inherent scalability that would be necessary if our app was used at any testing centers.

Continuous Integration and Deployment (CI/CD)

We decided to leverage GitHub Actions because of the CI/CD capability where any changes we pushed to our Streamlit application repository were automatically deployed to GCP.

Machine Learning

Datasets

We used the crowdsourced Coughvid dataset which was created by a team of researchers from EPFL providing over 20,000 crowdsourced cough recordings representing a wide range of ages, genders, geographic locations, and COVID-19 statuses. After cleaning and balancing the dataset for our specific use case, we ended up with 699 samples for each class: healthy, symptomatic and COVID-19 positive, out of which 559 were assigned to the training set using an 80/20 random train-test split. We then augmented this data for classes for which we did not have more samples available by adding random permutations (Gaussian noise, time shifts, time stretches, and pitch), making sure to apply random permutations to an equal number of samples in each class. This resulted in a balanced training dataset with 1677 samples for each class and a non-augmented, balanced testing set containing 140 samples for each class.

Feature Selection

When it came to feature selection we had to be thoughtful in how we iterated on our model. First, we wanted to provide interpretable predictions to our users while ensuring that our approaches were grounded in the medical literature on COVID-19. Secondly, we were working with limited, augmented data, hence we wanted to ensure that our model was focusing on the relevant parts of the cough sounds instead of overfitting to any noise. After trying out multiple models, we chose a shallow gradient boosted decision tree model that used three categories of features to provide a COVID-19 prediction: embedding-based features, audio features, and clinical background information.

-

Embedding-Based Features

When a user submits a cough, our model extracts an 128-vector embedding of the audio data using a computer vision model named VGGish, all in the cloud. Through our research, we recognized different patterns in a healthy person’s audio embeddings when compared to a COVID-19 positive individual’s audio embedding. Therefore, we used specific segments of audio sample embeddings as features to help our model gauge the risk factor that the user has COVID-19.

-

Audio Features

When a user submits a cough, our model calculates various measurements that help capture what the medical community has identified as a dry cough associated with COVID-19 infection. Specifically we consider the maximum signal, median signal and spectral bandwidth of an audio recording, which stand for the loudest point of the audio, the average loudness of the audio, and the standard deviation of a cough’s audio frequencies over time, respectively. We use these metrics as features in our model.

-

Clinical Features

Lastly, our app uses clinically relevant background information provided by the user to make better predictions. These features are the patient’s age, history of respiratory conditions and current fever and muscle pain statuses.

Model Iterations

First Interation Cycle

Our first iteration of the model involved performing a simple logistic regression on Mel-Frequency Cepstrum Coefficients (MFCC) features extracted from a user’s submitted cough. We sourced this initial feature set from Coughvid’s public repository. Using this baseline model, we were able to achieve a 60% ROC-AUC score on the binary classification task of predicting whether a user was healthy (including symptomatic COVID-19 untested users) or COVID-19 positive. We used the SHAP library to interpret our model and evaluate which features were most important, enabling us to find that the model was focusing particularly on the spectral bandwidth of the cough sample.

Second Interation Cycle

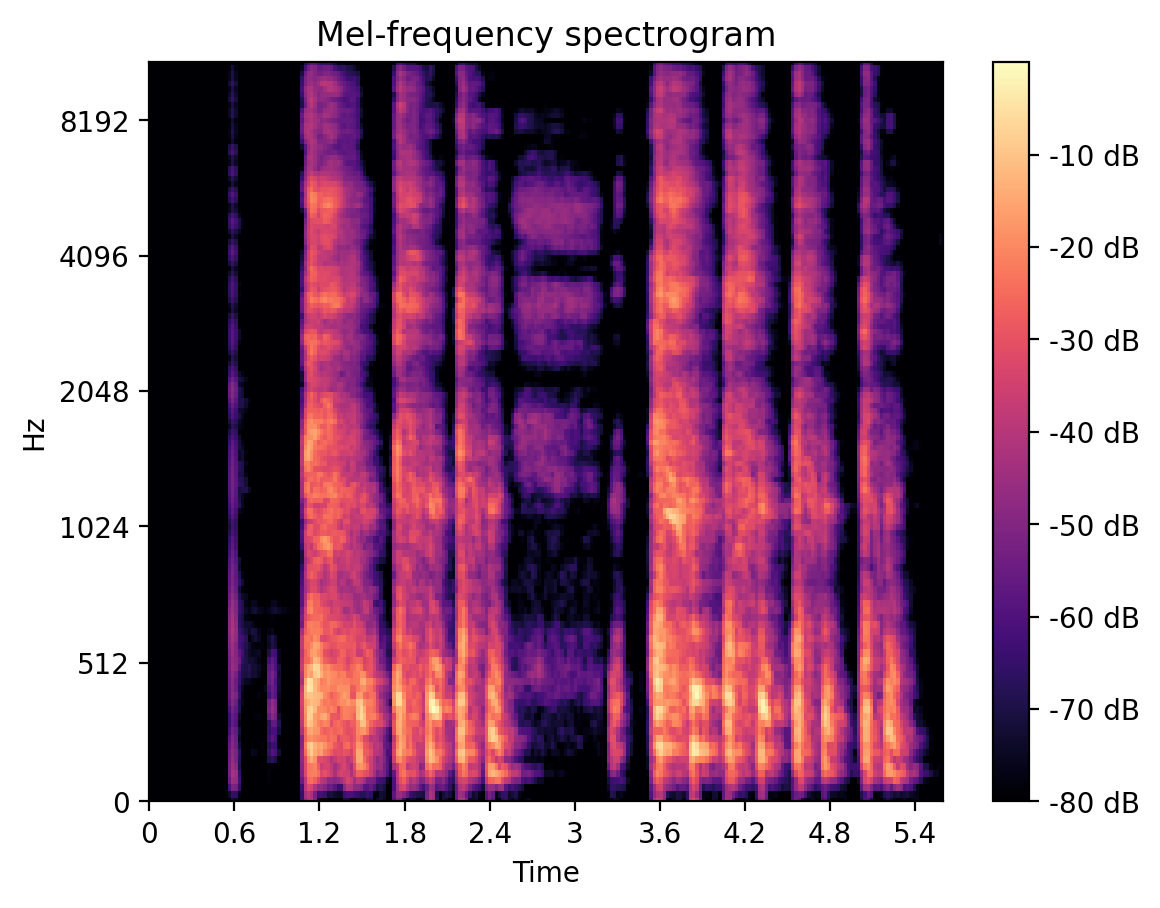

For our second iteration we decided to build a multi-class model as it was important to us to distinguish between COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 symptomatic (which includes some flu symptoms) but untested individuals. To achieve this goal, our model was trained to predict one of the three classes healthy, COVID-19 symptomatic, and COVID-19. As part of this process, we created a deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) built on top of Resnet-50, where the input was the user submitted cough audio mel-frequency spectrogram (see Figure 2.). This model achieved significant accuracy on the training data, however we failed to regularize the model sufficiently in order show promising validation results.

Third Interation Cycle

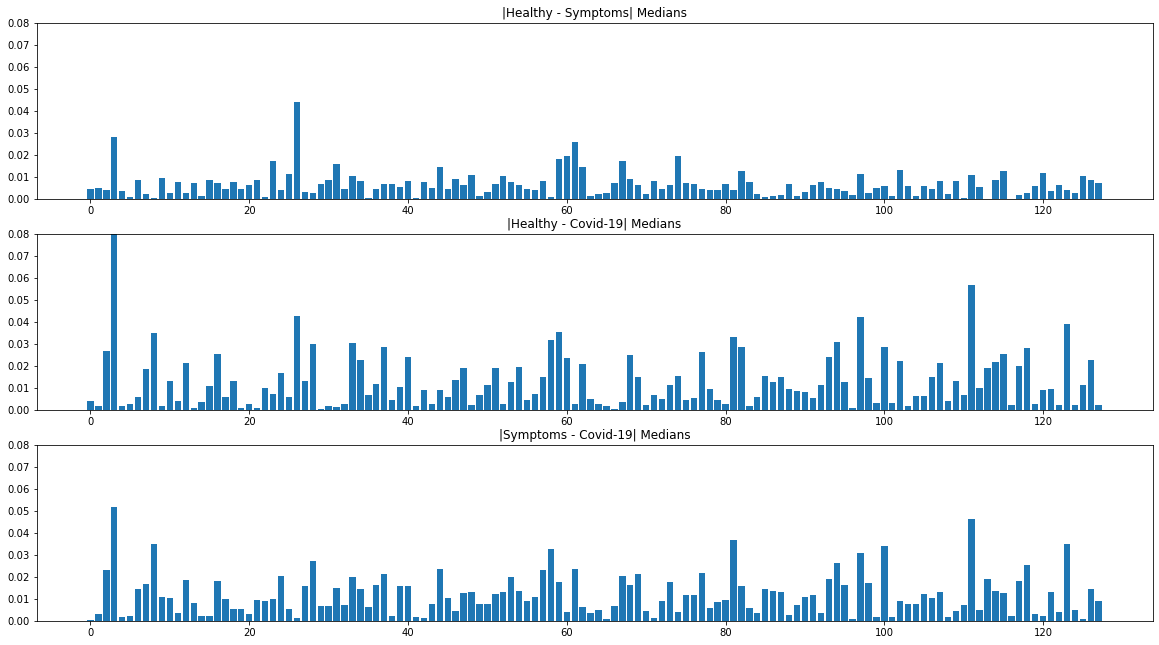

The third iteration produced the model we currently have deployed. Using our learnings from the past two iterations, we expanded our feature set by incorporating VGG-ish embeddings, a narrowed-selection of audio features (including the spectral bandwidth), as well as the clinical background information provided by the user. One of the methods to identify differences in the 128-vector embeddings between the three classes was to look at the absolute deviations in the medians for each pair of classes (see Figure 3.). In order to prevent overfitting, we chose to train a shallow gradient boosted decision tree model which achieved high validation accuracies in the multi-class setting.

Figure 2. A Typical Mel-Frequency Spectrogram of a Cough Recording

Figure 3. Absolute Deviations in the Medians of VGGish Embeddings Between the 3 Classes

System Evaluation

Model Performance

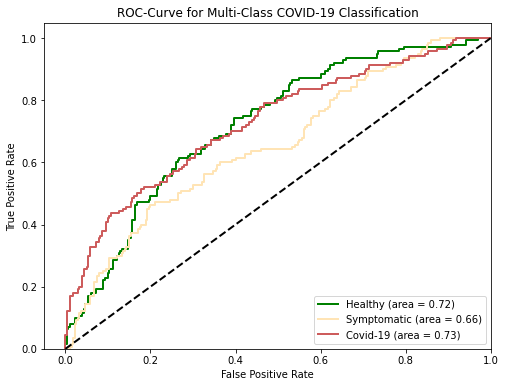

Considering overall performance, our model is achieving a multi-class ROC-AUC of 71% as broken down in Figure 4. which is a strong improvement over our baseline logistic regression algorithm (60% ROC-AUC). A class that is particularly important to attain high accuracy on is the symptomatic class, which represents users from our dataset who were symptomatic but did not have COVID-19 or had not yet received a COVID-19 PCR test result.

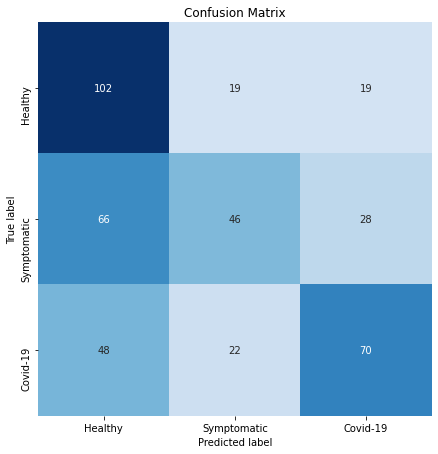

Considering the validation set performance we are excited that our model is quite accurate in predicting a user is healthy given he or she is indeed healthy (high recall on class “healthy”), as shown in the confusion matrix in Figure 5. In addition, given a model predicts one has COVID-19, there is quite a high chance that a person actually has COVID-19 (high precision on class “COVID-19”). At the same time, we recognize that there is a lot of room for improvement, especially for symptomatic patients who may have a cold or pneumonia, but not COVID-19.

Characteristic (ROC) Curve for the 3 Classes

User Experience

To make sure our app met the usability requirements for the audience we initially targeted, we have run a series of user experience experiments. Our results indicated that our test users were initially confused about the wording used in our application and the different user flows offered. We have since addressed these issues by simplifying the language and our user interface as much as possible in the context of a non-deep-linking single page application (SPA).

Application Demonstration

Use Case 1: Getting a COVID-19 Risk Assessment as a New User

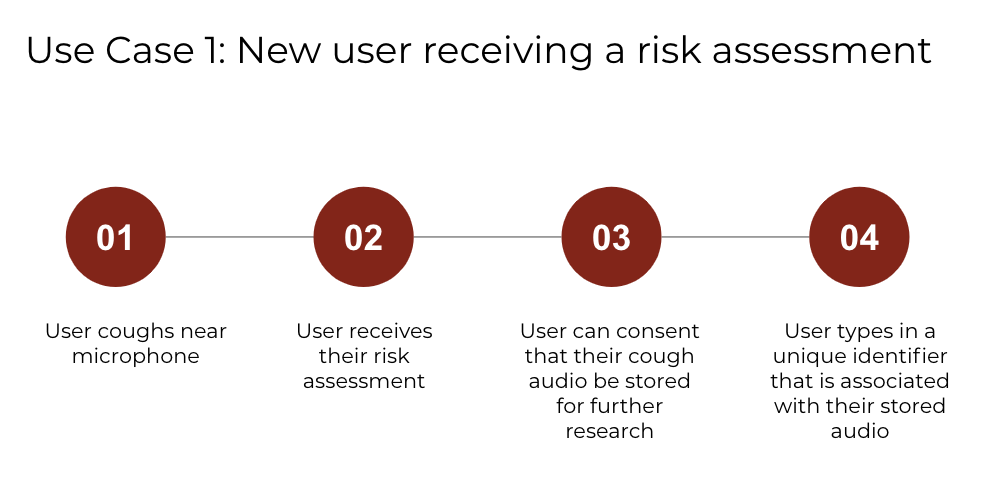

The main utility of our app is to provide users with a risk assessment of their COVID-19 status. We decided to build a web application to make sure our application was ubiquitously used and to avoid the perils of low uptake which many COVID-19 screening mobile apps experienced. We achieve this in 4 steps, summarized in Figure 6. and shown in the app in Figure 7.

Figure 6. New User Journey to Get a COVID-19 Risk Assessment

(a) User coughs near the microphone.

(b) User receives their risk assessment.

(c) User consents to upload data for research purposes and learns more about the prediction.

(d) User types in a unique identifier so that future PCR results can be linked to the submitted data.

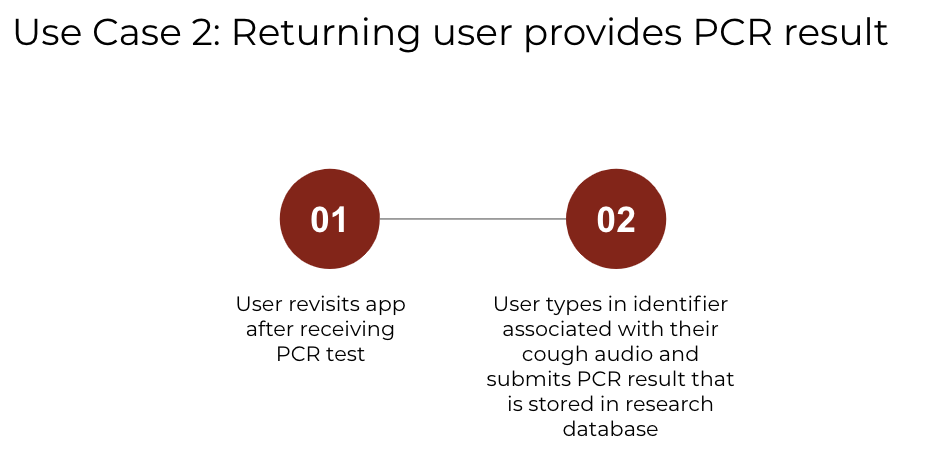

Use Case 2: Uploading PCR Test Results as a Returning User

The secondary goal of our app is to collect a large COVID-19 cough dataset. We achieve this in two additional steps to the new user journey, summarized in Figure 8. and shown in the app in Figure 9.

Figure 8. Returning User Journey to Upload a PCR Result

Figure 9. Use Case 2 Demonstration in Streamlit

Reflection

We learned so much while collaborating on this project and truly had an amazing time working together, even when things sometimes didn’t go as planned! Here is a summary of our key takeaways:

What Worked Well

-

Streamlit

Streamlit allowed us to quickly create an MVP with a decent-looking UI, which was awesome! Streamlit’s built-in functionality with Python libraries such as Matplotlib was really helpful, because we were able to transfer work from our model development notebooks into the ML production environment without the need for much change.

-

GCP AI Platform

Uploading models to AI Platform and letting it handle the serving and scaling problems for us without much cost was really helpful. We were able to complete this whole project just using the free tier in GCP with the initial $300 provided to each new account.

What Did Not Work As Planned

-

Latency on GCP App Engine

One issue that we had to deal with was significant latency that arose when we hosted our app on GCP’s App Engine because we could not use more powerful machines. Specifically, there were some operations we did not send to AI Platform but ran in the app instead, including the operations for displaying to users how we interpreted their cough using cough segmentation and mel-frequency spectrograms. These operations had a higher latency than we thought at first. When developing locally, we would add a feature that easily ran on our machines but observed high latencies once uploaded to GCP’s App Engine.

Next Steps

-

Improving Latency

We are currently exploring configurations for GCP App Engine that will allow us to better serve users with lower latency while at the same time reducing costs. We are also working on improving the caching within our Streamlit application to help combat latency issues.

EDIT: In the last 4 days since our public demo for CS 329S we have migrated our application to GCP Cloud Run and used more advanced chaching to reduce latency. We have achieved that our application now runs only with negilible latency and at less than 1/10 of the initial costs.

-

Improving Model Accuracy

One of our goals for our project is to facilitate the collection of crowdsourced COVID-19 cough datasets because we experienced how difficult it is to train an accurate model with limited data. However, we also recognize that there are changes we can make to our model which will improve its performance on the currently available data and we look forward to conducting more experiments.

Broader Impacts

When we first learned about the possibility of detecting COVID-19 from cough recordings, we were immediately drawn to contribute in helping the world fight the pandemic. It was such a privilege to tackle this challenge while learning about the process of designing end-to-end, user-centric machine learning systems.

As a team, we recognize that providing someone a COVID-19 risk assessment is not a task to take lightly as mispredictions can be very harmful. To make our intent and accuracy levels clear, we made sure to include disclaimers and related extra information about our algorithms, extracted features, and model performance transparently in our app. Therefore, in our design decisions, we chose to focus on creating an application that was informative and interpretable. Furthermore, people’s COVID-19 statuses are sensitive data so we only use all information for the specific purpose it was collected for.

While we believe this project is a start in the right direction, we recognize there are more improvements to be made before our application is ready for the real world, most importantly higher prediction accuracy.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the teaching staff of CS 329S, Chip, Karan, Michael (our project mentor) and Xi for all their support throughout this project.

Thank you Amil Khanzada and the Virufy team for promoting work on COVID-19 risk prediction using cough samples.

References

[1] The Coughvid dataset which we used for training and testing examples: The COUGHVID crowdsourcing dataset: A corpus for the study of large-scale cough analysis algorithms (Zenodo)

[2] The Coughvid Repo which provided us feature extraction for training our first iteration of models and heavily influenced our research: COUGHVID · R10770 (c4science.ch)

[3] The Coughvid team’s current application (check it out!): Coughvid (epfl.ch)

[4] A tutorial provided to us in class by Daniel Bourke which we referenced when building our end-to-end system: mrdbourke/cs329s-ml-deployment-tutorial: Code and files to go along with CS329s machine learning model deployment tutorial. (github.com)

[5] In order to create our application we used Streamlit: Streamlit • The fastest way to build and share data apps

There are various papers we referenced during research which helped us improve our model including:

[6] Exploring Automatic Diagnosis of COVID-19 from Crowdsourced Respiratory Sound Data

[7] Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition

[8] COVID-19 Sounds App - University of Cambridge (covid-19-sounds.org)

[9] AI4COVID-19 - AI Enabled Preliminary Diagnosis for COVID-19 from Cough Samples via an App

[10] CNN Architectures for Large-Scale Audio Classification.

Let’s defeat the pandemic!