An active data valuation system for dashcam data crowdsourcing

App link

The Team

- Soheil Hor, soheilh@stanford.edu

- Sebastian Hurubaru, hurubaru@stanford.edu

Problem definition

Data diversity is one of the main practical issues that limits the ability of machine learning algorithms to generalise well to unseen test cases in industrial settings. In scenarios like data-driven perception in autonomous cars, this issue translates to acquiring a diverse train and test set of different roads and traffic scenarios. On the other hand the increased availability and reduction in cost of HD cameras has resulted in drivers opting to install in-expensive cameras (dash-cams) on their cars, creating a potential for a virtually infinite source of diverse training data for autonomous driving applications. This data availability is ideal from a machine learning engineer’s point of view but the costs in data transfer, storage, clean up and labeling limit the success of such uncontrolled data-crowd-sourcing approaches. More importantly, the data-owners might prefer not to send all of their data to the cloud because of privacy concerns. We propose a local unsupervised dataset evaluation system that can prioritize the samples needed for training of a centralized model without the need for uploading every sample to the cloud and therefore eliminate the costs of data transfer and labeling directly at the source.

System design

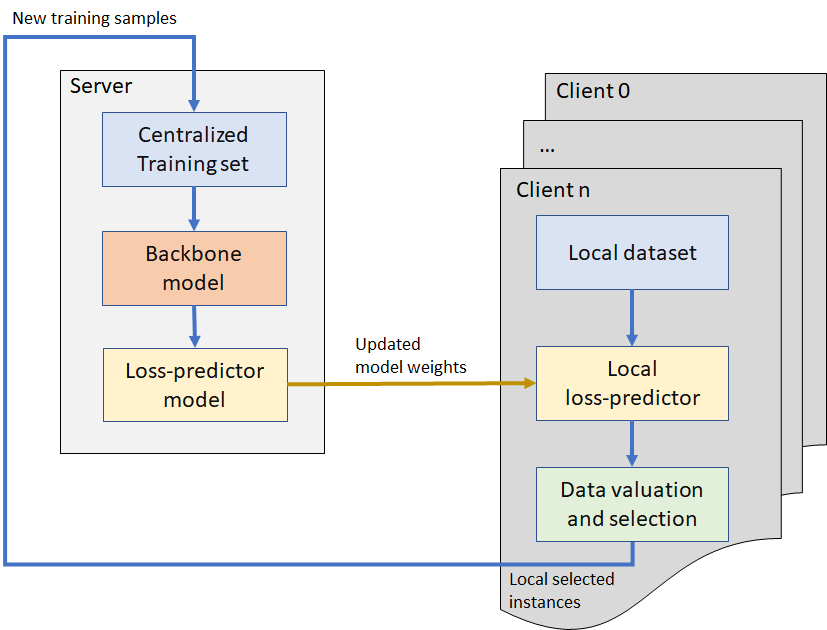

As it was explained our goal is to optimise the training set corresponding to an ML model by distributed data valuation. One of the well-known approaches to this problem is to prioritise the samples based on their corresponding model uncertainty. Our proposed approach is using a local “loss-predictor network” to quantify the value of each sample at each client before its transmitted to a central server. The proposed system consists of two main modules: namely the centralized server and the local data source clients. Please see figure 1 for more details.

Module 1: The Centralized server

The goal of the server module is to:

- Gather data from different data sources (clients),

- Retrain and update the backbone model based on the updated training set (for labeled data)

- Train the loss prediction module based on the updated backbone model

- Transmit the weights of the updated loss prediction module to each client

Module 2: Local data source clients

The goal of each client is to:

- Estimate the backbone model’s loss for each local sample using the local loss-prediction model

- Select the most valuable (valid) samples based on the predicted loss

- Transmit the selected samples to the centralized module

In order to make the system available to users, we chose AWS as our cloud platform. Once a user decides to upload any data with us, this gets stored on AWS S3. In order to deal with the concurrency issues, which arise when multiple users share the data with us, we created a scheduler using AWS CloudWatch that triggers the online learning at a specified time interval. The centralized server which does the online learning, was implemented as a Lambda function, configured with a Docker image runtime. By using the scheduler and allowing at any time just one instance of the online training, all the new available data will be processed once and the new model will be made available to all clients at the same time. Now, as the model gets trained, we wanted to prevent users from actually being able to evaluate and upload data with us, as this would enable them to still be rewarded for some data, that after the training can be worthless. To enable this, we used AWS IoT to push data from the online learning Lambda function to all running clients, containing all the training stats and progress, based on which the client will decide when to make the platform again available to the users.

As client data privacy was our main concern, when users evaluate pictures this has to happen without sending any data to us. Therefore the online learning component generates at the end a browser ready model, and uploads it to AWS S3 with a new incremented version. Whenever a client would like to evaluate some data, there is a check to assess whether a new version is available and always get the newest model version. All of this was done using TensorFlow JS.

In order to protect the data from the outside world, and only allow access to the resources over the web app for all unauthenticated users, AWS IAM was employed and with CloudFormation configuration files we could set up the full security layer automatically.

Now in order to create all the infrastructure automatically based on the code changes, allowing us to have both a test and production environment, we have employed an infrastructure as a code approach. For this we used AWS Amplify and AWS SAM allowing us to leverage AWS CloudFormation services.

Machine learning component

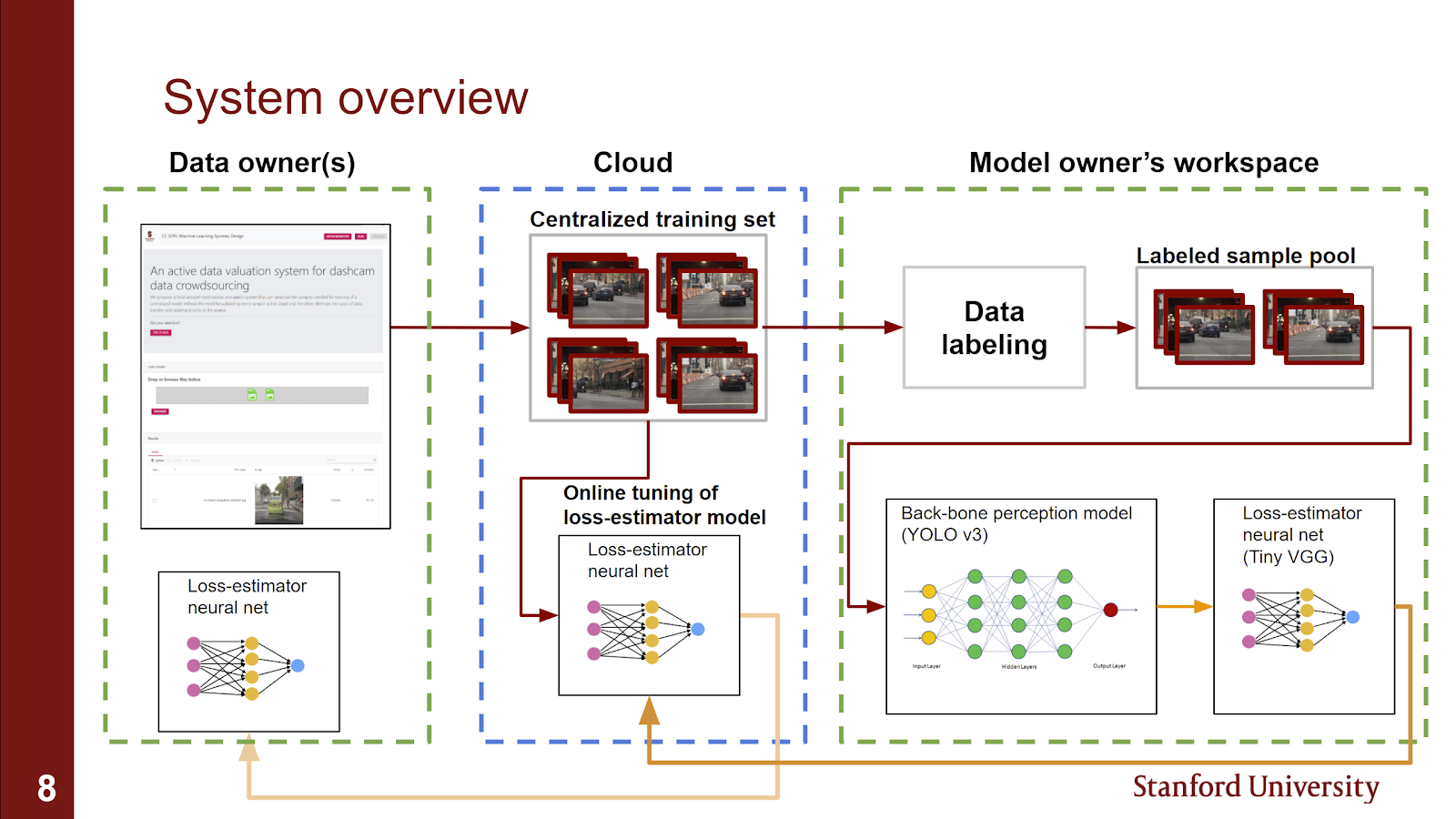

Our approach to the on-the-edge data valuation problem is based on recent advances in development of loss-predictor models[]. In simple words, a loss predictor model is a model that tries to estimate another model’s loss as a function of its inputs. We use the loss of the model as a measure of model uncertainty that can be calculated without access to the ground truth labels enabling evaluating each sample directly at time of capture.

For the back-bone model we converted a pre-trained YOLO-V3 [1] directly from the original dark-net implementation. Then we evaluated the converted model on a dashcam dataset available publicly online (bdd100k dataset available at https://bdd-data.berkeley.edu/)

For the loss predictor model we decided to go with a small CNN that can be directly implemented on the browser (Tiny-VGG). We trained the Tiny-VGG model on the classification loss resulting from running the backbone model on unseen data.

The implemented system has 2 interconnected training loops:

First the “Offline” training loop that requires labeled data and can help in training of the loss predictor model to be a better predictor of the loss of the backbone model. Since our system did not include a labeling scheme we trained this loop only once (using a labeled subset of the bdd100k dataset) we then used the learned weights as the starting point for the second training loop (online learning).

For the online learning training loop we start with the weights extracted from the offline training phase and then retrain the loss-predictor model whenever the centralized unlabeled dataset is updated. The challenge here is how to retrain the loss predictor model on these samples without having access to the labels. The way that we approached this problem is by considering the fact that the backbone model’s loss on these samples will be zero once they are labeled and added to the backbone model’s training set. Based on this assumption we decided to use the new samples with loss of zero as an online learning alternative to the larger offline learning loop.

System evaluation

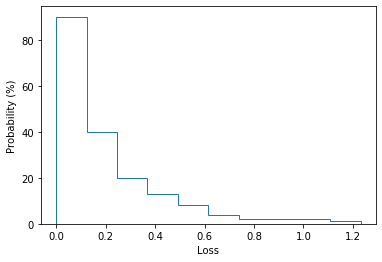

One of our main challenges was to map a measure like the loss of a model to a quantitative and fair value in dollars. For this task we first did an empirical analysis of the distribution of the classification loss values of the backbone model. Figure 3 shows the empirical distribution of losses for the YOLO V3 model. We used this empirical probability distribution to calculate how likely is observing each sample in comparison to a randomized data capture approach with uniform probability of observing each sample. We defined the value for each sample as follows:

In which  is the empirical probability of each loss as shown in Figure 3,

is the empirical probability of each loss as shown in Figure 3,

is the probability that each loss would be observed if the loss distribution was uniform (10% for the 10-bin histogram shown in figure 3) and BSV is the “Base Sample Value” chosen by the system designer. Based on our initial research the value that companies like Kerb and lvl5 have assigned to dashcam videos is around 3$ per hour of video recordings which roughly translates to 0.1 cent per frame assuming a 1fps key-frame extraction rule. However since in our system the samples are assumed to be much more diverse than a video and we require manual selection of the samples by the user we assumed a 10 cent base sample value for each frame.

We observed one caveat for this method in practice: Because even the smallest losses have a non-zero value (because probability of observing any loss is non-zero) the already-sold samples could monetized again if the loss-predictor model does not give exact zero loss for its training set (which can be the case in online learning). We dealt with this problem by adding a “dead-zone” to our valuation heuristic in a way that samples with losses less than a specific threshold would have zero value (in our latest implementation we found that a threshold of 0.27 to work well with our data).

Application demonstration

We made our application available online, to allow all users access to it. We have two links available, https://cs329s.aimeup.com for the production environment and https://cs329s-test.aimeup.com for the test environment. By choosing the production environment we click on the browse data button and load some on-the-topic pictures and hit the Run button:

We could see the model generated some scores which get mapped to a fair value in U.S. dollars. All this data can be exported to Excel/PDF by using the buttons available in the spreadsheet toolbar. Search is also possible, if any picture can be referenced by name, to avoid scrolling when using a large number of pictures.

After selecting one picture and uploading it, the online learning gets activated and the functionality on all clients is disabled during this time providing a real time progress of the training, as can be seen in the screenshot below:

To assess what is going on in the backend we have built a monitor page that can be opened by pressing the “Open Monitor” button. From that moment on, all the backend resources will push notifications to it. After uploading the picture and during the online training we can see the following:

After running the new model on the same pictures, the fair value of the uploaded pictures goes down to 0, meaning that the model has learned the features available in it.

Reflection

First challenge that we encountered is how to fetch a model from a secure site, where each file can get accessed over a secured private link and run it in the browser. TensorFlow JS unfortunately does not support this kind of operation, so we had to implement this ourselves.

One major drop back in our project was our third teammate suddenly dropping from the course. Which we could have seen coming from him not being responsive in the first couple of weeks of the quarter.

Another major challenge was dealing with model instability while retraining the loss predictor model in our online training loop. Our decision to also have the original training set to “refresh” the training helped a lot.

One issue that we did not count on was the fact that debugging an online learning system requires a very detailed logging and version control system that enables following the dynamic performance of the model. We ended up implementing a basic version of a logging system but still it was very hard to predict how the model would behave after a few retraining sessions.

Infrastructure as a code, is a powerful tool, that does more than one would expect, but can lead to unexplainable behavior. Two examples that gave us some headaches:

- one cannot rely on the fact that data on the temporary folder inside a Lambda function container persists between the calls

- AWS S3 still delivers cached data to you, despite calling the API with caching disabled. Just deleting the files and uploading them again helped!

Given unlimited time and resources we would incorporate a labeling block into the system and close the loop on active data capture and labeling by retraining the backbone model on the centralized training set.

Broader Impacts

Since our valuation system is fully automated and does not have access to labels for the input data it could be manipulated in many different ways. For instance, one could monetize several copies of the same image (or maybe slightly different versions of one image) and leverage the fact that the loss predictor model can not be trained separately for each individual image. Or because the values are assigned to samples based on how unexpected each sample is, out of context samples can be easily monetized if the users intend to trick the system. The way that we have dealt with this issue is by first, limiting number of uploads that a user can do to an upload attempt every 5 minutes, and we also train the loss-predictor model between different uploads in order to reduce the loss values corresponding to all of the uploaded samples at each iteration. As a result, the users will be able to monetize unrelated or repeated images only once.

Detecting repeated or unrelated images can be pretty straightforward using irregularity detection methods like one-class SVM but we have not currently implemented such a method.

References

[1] Redmon, Joseph, and Ali Farhadi. “Yolov3: An incremental improvement.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).